Milk Pricing– The Great Unknown

Financial Literacy

Several years ago, I worked with my milk coop to forward contract some milk. I called the coop milk pricing, a forward contracting expert, to explain the numbers. The comment I got was, “It’s a long formula, and I can’t explain it”. Needless to say, I was a little frustrated with that answer.

I have to say that today there is a stronger push to be more transparent with milk pricing, but it is still many times a wonderful mystery. We are in the process of updating the Federal Milk Marketing Orders (FMMO) which has not been reformed since 2000. The results of this reform are yet to be revealed, but there are a lot of stakeholders as part of the process.

All milk prices for the farmer are noted in hundredweights (CWT). This is the standard unit that most farmers understand when talking about milk pricing. While the general public refers to milk by the gallon, which is 8.6 pounds, most farmers only think of it in pounds or hundredweights.

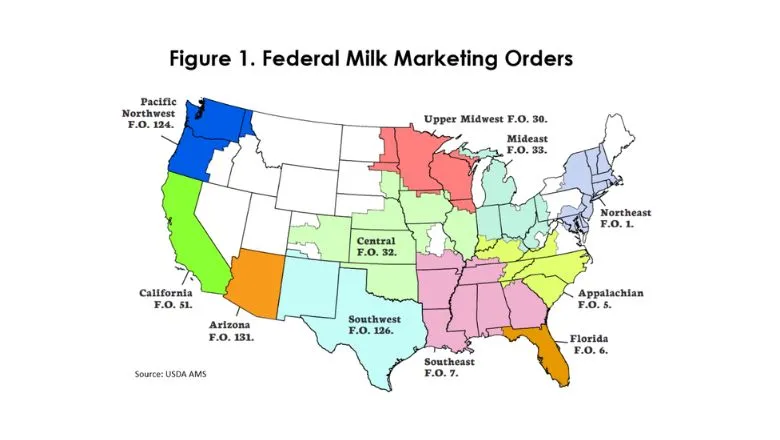

There are currently 11 FMMOs in the U.S., and about 2/3’s of the milk in the United States is marketed through them. The rest is marketed independently outside of the FMMOs. The chart below shows the distribution of each order:

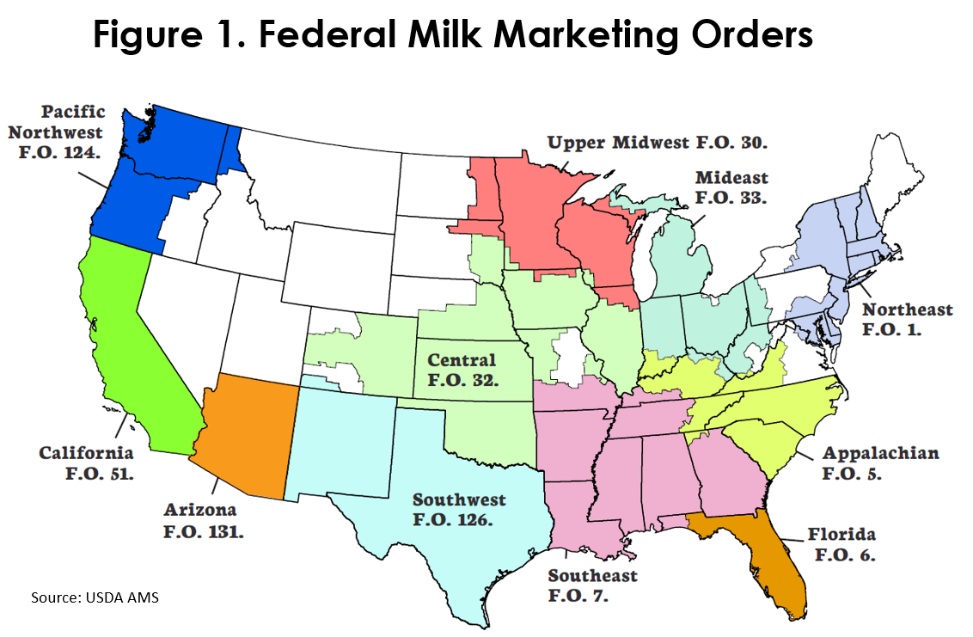

There are 4 classes of milk:

- Class I: fluid milk

- Class II: soft products like ice cream, yogurt and cottage cheese

- Class III: hard cheeses, cream cheese and whey

- Class IV: butter and dry products such as milk powder/NFDM

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) Market is where futures are bought and sold. Anyone, Farmers, and speculators can work through a broker and buy and sell on the CME exchange. They market Class 3 and Class 4, Non-Fat Dry milk, Butter, Cheese Blocks, and Cheese Barrels. The markets are settled each month, and the price is announced by the USDA-Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS). Even though they are separate marketing points, they are connected since they are all derived from one raw commodity, milk. The Class 1 price is derived from the average of Class 3 and 4 plus 74 cents. This formula changed with the 2018 farm bill and there is talk of changing it back to the previous formula that uses the higher of Class 3 or 4 as the Class 1 mover.

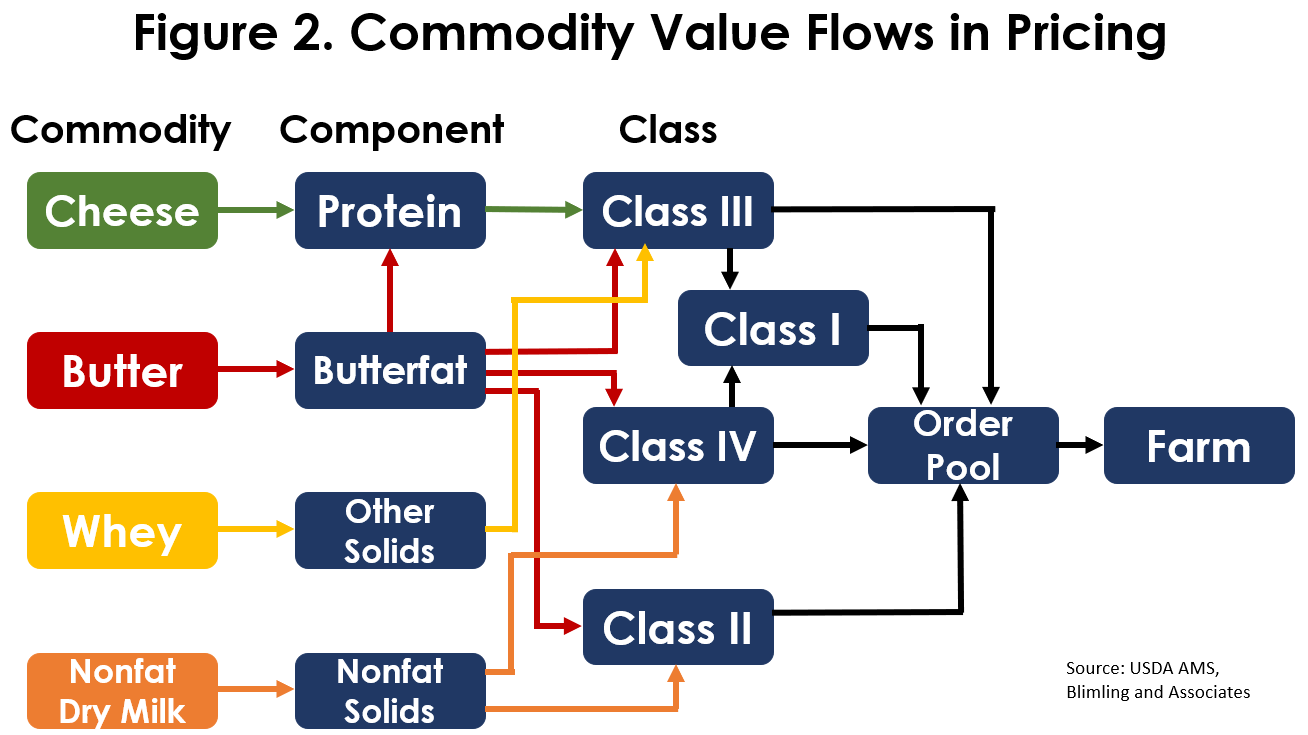

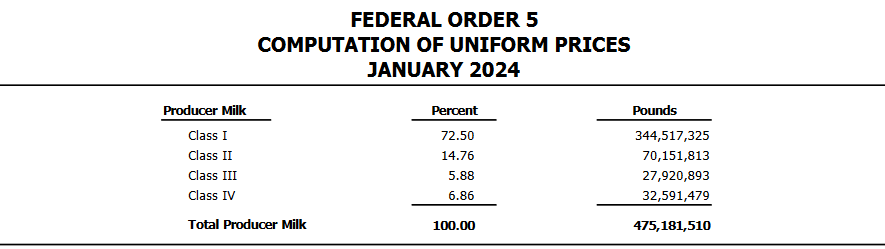

Each FMMO pools there milk each month by the end use of milk produced to come up with a uniform blend price that is different in each FMMO. The southeast typically has a higher percentage in Class 1, and midwestern states are typically higher in Class 3, but the actual amount fluctuates monthly and annually with consumption and production patterns. As you can see from the chart below, FO5 had a 72.5% utilization rate in January 2024. All of these market prices can be found on the Market Administrator’s website: www.malouisville.com/

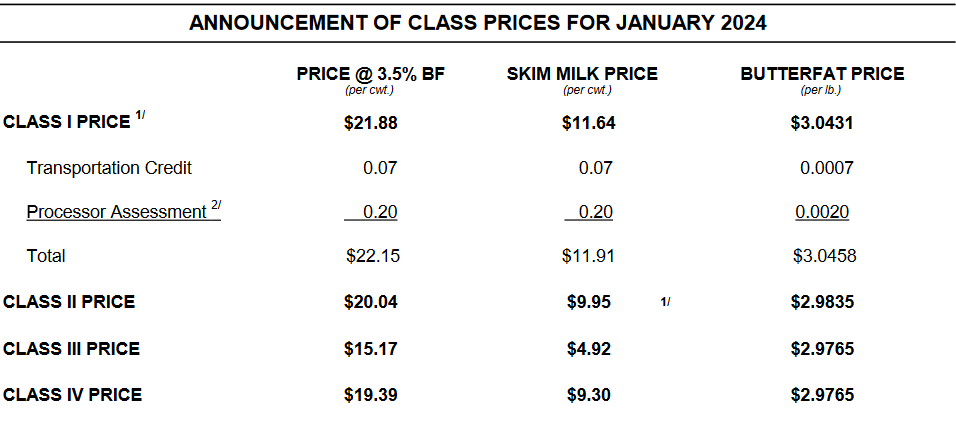

Federal Order 5, which is most of the milk produced in Virginia, with the exception of a few northern Virginia farms pays farms a skim milk and a butterfat price. In addition, farms are given a transportation credit and a processor assessment from the federal order. All of this is taken into consideration to come up with a uniform blend price for the entire federal order. In other parts of the country, milk is priced on components, Butterfat, and Protein, with protein being a significant factor in the price.

Once the blend price is announced, the farm's buyers then come up with a pay price for the farmers. In most cases, the milk is marketed through a cooperative. The cooperative needs to factor in hauling, marketing, and promotion assessments that are deducted from the farmer's checks. Each coop manages these costs independently. Some coops also add volume and quality bonuses for farmers as an incentive to produce a consistently high-quality product.

When you ask a farmer how much they got for their milk, they often refer to the “mailbox” price. The Mailbox Price is defined as the net price received by producers for milk, including all payments received for milk sold, and deducting costs associated with marketing the milk. The Agricultural Marketing Service reports the average mailbox price for each federal order and larger reporting states. Again, this price can vary from farm to farm based on actual butterfat and protein percentages, milk quality and transportation costs.

There are a lot of people and agencies involved in the pricing of milk. Because milk is a highly perishable product and it is a large percentage water, its pricing can become quite complicated. While the movement of milk across federal order lines can complicate the process there is always an accounting of where it went. Milk pricing can be complicated and difficult to understand, but there are a lot of checks and balances to ensure that it is priced fairly.

Author:

Jeremy Daubert

Extension Agent, Agriculture and Natural Resources Dairy Science

Virginia Cooperative Extension

Harrisonburg, VA